My Memories of Maulana Azad

Category:

R C Mody is a postgraduate in Economics and a Certificated Associate of the Indian Institute of Bankers. He studied at Raj Rishi College (Alwar), Agra College (Agra), and Forman Christian College (Lahore). For over 35 years, he worked for the Reserve Bank of India, where he headed several all-India departments, and was also Principal of the Staff College. Now (in 2010) 84 years old, he is busy in social work, reading, writing, and travelling. He lives in New Delhi with his wife. His email address is rmody@airtelmail.in.

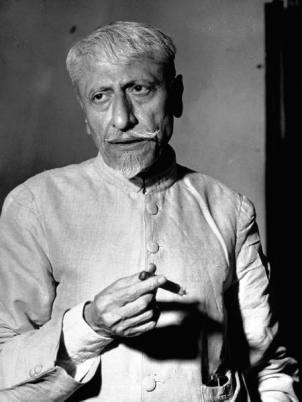

![]() Abul Kalam Ghulam Muhiyuddin, who was better known as Maulana Azad, was one of the leading figures of the Indian freedom movement. He became President of the Indian National Congress in 1923, when he was less than 35 years old, being the youngest ever to occupy that position.

Abul Kalam Ghulam Muhiyuddin, who was better known as Maulana Azad, was one of the leading figures of the Indian freedom movement. He became President of the Indian National Congress in 1923, when he was less than 35 years old, being the youngest ever to occupy that position.

But it was not until 1940, when he was elected as Congress President for the second time, that he became known to me and others of my generation. This time he was elected effectively in place of Subhas Bose who was forced to resign a few months after his re-election in 1939 (in between Dr. Rajendra Prasad held temporary charge).

Maulana Azad's second term as Congress President was the longest ever in the history of Congress, before Sonia Gandhi's term six decades later. He remained in this position for six years, till 1946, as the Congress could not hold an election for its Presidentship because its senior leaders were in jail during most of the intervening period.

Azad was thus at the helm of the Congress during the crucial years preceding transfer of power. This, no doubt, contributed to his stature and to his place in history. He captured our imagination first in April 1942 when he led the Congress in negotiations with Sir Stafford Cripps. Cripps had come from England with proposals to create a self- government by Indians at the Centre ‘here and now', with an understanding that India would attain Dominion Status (close to independence) immediately after the end of the War. As is well known, Cripps' proposals were turned down by Congress, with Gandhi calling them ‘a post dated cheque on a crashing bank'.

Maulana Azad emerged from the failed negotiations as a much taller figure. He had conducted himself with confidence and dignity all through the deliberations, as evidenced by reports and pictures appearing in the newspapers and from the documentaries released by the Government's film division. We would see him alighting from his car in the compound of 3, Queen Victoria (now Dr Rajendra Prasad) Road, New Delhi where Cripps was holding the historic talks, looking majestic.

He would be accompanied by Asaf Ali, who was acting as his interpreter. It became known then that Azad did not know English well enough to be able to carry on serious negotiations in that language. But this did not go against him in the eyes of public, even though most of India's leaders at that time were known for proficiency in English, having studied in Britain. Instead, he looked more dignified on that account. The esteem in which he was held by Cripps, and in later years by Wavell and Pethick-Lawrence, became public knowledge. He was known for his intellectualism and erudition, and that made up for his lack of proficiency in English language.

A few months after we acquired familiarity with him, in early 1942, Azad disappeared from the scene for almost three years. He was arrested, along with most other senior leaders because of their participation in the Quit India movement in August 1942. We had an idea that he was incarcerated along with Nehru and most of the members of the Congress working committee in the Ahmednagar Fort. (More was known about it after the publication of Nehru's Discovery of India in 1946 while details became public many years later, after the publication of Azad's book India Wins Freedom in 1958). The only news about him I heard during the three years of his incarceration was when his wife died and he was not permitted to meet her before her death. They had no children.

Azad, along with his colleagues, was released from the prison in June 1945. From then on till May 1946, he dominated the Indian political scene. He was during this period of nearly one year undoubtedly one of India's Big 4 Leaders - the other three being Gandhi, Jinnah and Nehru, with no one who appeared to be a close fifth. (Sardar Patel's emergence as one of India's Big 3, soon after independence could not be visualized during this period at that time.)

Soon after his release from prison, Azad travelled to Simla for what is now called the first Simla Conference of June 1945. It was my summer vacation and I had gone to Simla to watch the historic event from outside Hours before Azad's car was due to arrive in Simla from Kalka, crowds had gathered around the Cecil hotel, where he was to stay. During the wait, which was much longer than expected due to crowds en route, the politicians at Simla were delivering fiery speeches elaborating Azad's services and sacrifices (including his not being permitted to be at his dying wife's bed side) for the nation. As his car approached its destination, it was dark and many faces that were trying to peep in got rubbed against the glass panes of the car windows. With difficulty, he could be conducted to his room in the hotel.

Then started a clamour for his Darshan. The crowds were told that he was tired and unwell and they would be able to see him only the next day. But they would not accept this. Ultimately, Azad appeared on terrace of the hotel's porch, covered in an ornamental Kashmiri shawl, amidst loud cries of Zindabad. He spoke for about 5 minutes in a measured tone. He said that he was physically a broken man after long incarceration and personal tragedy He asked the people to wish that he remained well enough during the following days, so that he could carry out the mission on which he had come.

The conference commenced at the historic Viceregal Lodge the next day. Nehru had not been invited for it. The only invitees were the presidents of all India political parties, and premiers of provinces, including ex-premiers of eight provinces, which were without responsible governments since Congress ministries had resigned in 1939 (these included stalwarts like C. Rajagopalachari, Govind Ballabh Pant, Dr. Khan Sahib and B. G. Kher). Gandhi had been invited but he did not attend the conference\; he met the viceroy separately a day before it started.

I saw Azad the next day entering the Viceregal Lodge in a rickshaw amidst slogans of Hindustan ka be-taj badshah zindabad (Long live the uncrowned king of India). I found him responding with a blushing smile. We read in the newspapers the next day that the Muslim League President Jinnah refused to shake hands with Azad when they met at the Conference. The Conference ultimately ended in failure after a few days, as Congress did not accept Jinnah's claim to be the sole representative of Indian Muslims and his insistence on nominating all the Muslim members of the proposed Executive Council.

During his return journey to Calcutta, Azad's hometown, his train passed through Aligarh. A huge contingent of rowdies from the local Muslim University came to the railway station and attempted to pull Azad out from his compartment and humiliate him on account of his stand against the Muslim League at the Simla conference. The situation was saved by police intervention. Thus ended the first phase of Azad's activities in the immediate aftermath of his release from detention.

His stature grew immensely during this period of less than a month. Meanwhile, Muslim League leaders were daily trying to denigrate him. "He does not have even four Musalamans behind him," they would say, showing four fingers of their hands. Jinnah coined for Azad a derogatory title, ‘Show boy of the Congress'. But Azad invariably ignored such remarks and never said anything derogatory about Jinnah then or at any time later.

Azad started making headlines once again in February 1946 when the British Cabinet Mission, headed by Lord Pethick-Lawrence, Secretary of State for India, arrived in Delhi. The Mission had two other members, one of them being Cripps, with whom Azad had negotiated four years earlier. The Mission's objective was to decide, once for all, the long pending issue of India's independence. All the members of the Mission and Viceroy Wavell, who acted virtually as the fourth member, were beholden to Azad all through the protracted negotiations, which were carried on for three long months first at Delhi, then at Simla and again at Delhi.

The result of these negotiations was the May 16 1946 Plan, which rejected clearly the demand for Pakistan. Instead, it proposed a three-tier structure. (Editor's note: Excerpts from the Plan are included below.)

15. We now indicate the nature of a solution which in our view would be just to the essential claims of all parties and would at the same time be most likely to bring about a stable and practicable form of Constitution for all India.

We recommend that the Constitution should take the following basic form:

(1) There should be a Union of India, embracing both British India and the States which should deal with the following subjects: Foreign Affairs, Defence, and Communications\; and should have the powers necessary to raise the finances required for the above subjects.

(2) The Union should have an Executive and a Legislature constituted from British Indian and States' representatives. Any question raising a major communal issue in the Legislature should require for its decision a majority of the representatives present and voting of each of the two major communities as well as a majority of all members present and voting.

(3) All subjects other than the Union subjects and all residuary powers should vest in the Provinces.

(4) The States will retain all subjects and powers other than those ceded to the Union.

(5) Provinces should be free to form groups with Executives and Legislatures, and each group could determine the Provincial subjects to be taken in common.

(6) The Constitutions of the Union and of the groups should contain a provision whereby any Province could by majority vote of its Legislative Assembly could call for a reconsideration of the terms of the Constitution after an initial period of ten years and at ten-yearly intervals thereafter.

16. It is not our object to lay out the details of a constitution on the above lines, but to set in motion the machinery whereby a constitution can be settled by Indians for Indians.

Source: http://www.bijosus.co.cc/sadna_gupta/CMP3_CabinetMissionPlan_16May.html

Provincial governments were thus to constitute the bottom (third) tier of the structure. Above them (second tier) would be the Group governments, each heading a group of provinces. Group A would include six Hindu majority provinces: Madras, Bombay, United Provinces, Bihar, Central Provinces and Orissa. Group B included Punjab, North West Frontier Province, and Sind. Group C consisted of Bengal and Assam. Finally, at the top (first tier) would be the Central government. The Central Government would deal with only Defence, Foreign Affairs and Communications. Most of the power would rest with the three Group governments.

Azad found the solution ideal and became its strong votary, while the Muslim League accepted it with mental reservations.

Nehru found the idea of a weak Central government atrocious. Yet Congress accepted the Plan, subject to some declared reservations. By July 1946, Nehru took over from Azad as Congress President. On July 10, 1946, Nehru addressed a memorable press conference at Bombay. From what he said at this Press Conference, he in effect meant that the issue of distribution of powers between governments at different levels remained open\; it was a matter ultimately to be decided, after the transfer of power, by India's Constituent Assembly, which would be a sovereign body. This totally upset the apple cart. The Muslim League withdrew its acceptance of the May 16 Plan. What happened subsequently is history.

With the virtual death of the May 16 Plan in July 1946, Azad, who had already ceased to be Congress President by then, overnight became, a non-entity on the Indian political scene. It is difficult to imagine how far he fell after being one of the Big 4 Leaders of India for almost a year. But it was not his fault. He had dreamt of a free and united India in which Hindus and Muslims would be near equal partners. Muslims would govern Punjab, Bengal, Sind, Assam, NWFP (as they existed then), and Baluchistan. Hindus would govern the rest. There would be, as per his concept, extreme cordiality between the two communities .That dream was now in a shambles.

Azad had little say in the discussions that followed, leading to partition of Punjab, Bengal and Assam and then of India itself. He was not in the picture when the June 3 1947 Plan was discussed with the British Government. He became the Member for Education in the Interim Government around October 1946, and became Minister for Education after Independence. He held this post until his death in 1958.

However, he was not completely out of the news all these years. In fact, soon after Independence, those very votaries of Muslim League (who had not migrated to Pakistan) who decried him as a ‘show boy' started calling him Imamul-Hind (suggesting that he was the supreme leader of India's Muslims). But Azad did not respond to this attempt to exalt him. He was wise enough to realize that leadership of Muslims in post-Independence India would not take him anywhere.

Still, occasionally, he did try to protect Muslim interest but in a subtle way. When Gandhi fasted in January 1948 to stop atrocities on Delhi Muslims and on certain other issues affecting them, Azad was by his side. Some mischievous elements rumoured that it was he who had drafted the conditions (which included release of Rs 55 crore due to Pakistan under the partition agreement but withheld by India due to the war in Kashmir) laid down by Gandhi for breaking his fast.

Later too Azad acted behind the scene on many occasions. It was said that after the Hari Das Mundra controversy in 1958, it was he who pressurized Nehru to drop T. T. Krishnamachari from the Cabinet. Earlier in 1956, when C. D. Deshmukh resigned from the Cabinet because of differences with Nehru and Pant, Azad opened up a new career for Deshmukh in the field of the Education, starting with his appointment as founder-Chairman of the University Grants Commission, followed by his appointment as the Vice-Chancellor of Delhi University. Azad had become Deshmukh's friend and admirer, with erudition and intellectualism being a common factor between the two.

Sardar Patel was designated India's Deputy Prime Minister after Independence and was unquestionably the most important man in India after Gandhi and Nehru. After Patel's death, there was a brief status war: Who was Number 2 in the Cabinet? No one was named as Deputy Prime Minister, and Nehru did not want to specify who was next to him in the Cabinet. It was reported that Azad once rushed to occupy the seat in the Lok Sabha next to the Prime Minister, before Rajaji, ex-Governor General, entered the House as the new Home Minister. (Cabinet Ministers sit in the House in order of their position in the Cabinet.)

Once Azad's name was rumoured for Presidentship of India, but he scotched the talk saying, "I would, no doubt, have a grand house to live in, but what would I do there?" The remark was not considered to be in good taste. In an editorial, the Statesman newspaper criticized it as trying to denigrate the office of the President.

Azad was last in the news when his book India Wins Freedom was released a few months before his death in 1958. The book evoked fierce controversy and suspense, the latter because of a stipulation that its last part would be released 30 years later, by which time all of the principal players in the drama leading to transfer of power would be gone from the scene.

I read the book shortly after it was released, about 52 years ago. I recollect that it brought out author's hostility towards Patel on various counts. There was also a complete absence of appreciation of any of Patel's role before and after Independence. For Rajendra Prasad and the Khan Brothers of NWFP, there was undisguised disdain. Gandhi has been depicted, at places, as inconsiderate and dictatorial, at other places as comical. For Nehru, Azad expressed warmth but blamed him for certain impetuous acts, particularly for his press conference of 10 July 1946, which led to demise of May 16 Plan and in a way for the Partition. Azad also referred to Nehru's fascination for Edwina Mountbatten. Two persons he praised are Pethick Lawrence and Wavell, for sincerity and uprightness.

I have gone through the pages of India Wins Freedom that were released 30 years later in 1988. I felt that they only highlight some of the points brought out in the original and lacked the sensation which they were expected to create.

When Azad died, after a brief illness, shortly after he was 69, the country mourned the passing away of a great Indian who for a short time strode the Indian scene, as well nigh a colossus.

Epilogue

Based on his book, I feel that Azad was an embittered man, and had not overcome his nostalgia for the May 16 Plan, till the end of his life. I believe that in his emotional attachment to this Plan he was starry-eyed, which clouded his better judgment and acumen as a statesman. As events unfolded in months and years subsequent to the announcement of this Plan, it can be easily surmised that India would have broken into splinters if the May 16 Plan had been adopted. The Muslim majority provinces would have come, at least initially, under the rule not of liberal Muslims like Azad but of rabidly communal leaders who ruled Pakistan after August 14, 1947, and who would have tried to wreck the country from within. With their additional say in a weak Central government, they would have played havoc with the country's armed services, its foreign policy, and many other sensitive aspects of its polity. We have to thank our stars that we were saved from this catastrophe.

Azad's role as Education Minister has been regarded by some as undistinguished. In the twelve years that he was Education Minister, there was no visible dent on the mass illiteracy in India. Others would say that the neglect was more on the part of Nehru rather than Azad. Nehru had given all his attention to planned economic development, probably with the feeling that illiteracy eradication would automatically follow. But the economy too grew very slowly, at the Hindu rate during Nehru years, not even keeping pace with the growth in population. The realization that not mere literacy, but good school education was vital to economic growth, came long after Nehru. Illiteracy eradication remained low on India's agenda for decades after both Azad and Nehru departed from the scene. Even with the benefit of hindsight, it is difficult to say who can be blamed for India's dismal failure on this vital front.

© R C Mody 2010

Comments

Add new comment